on patience

the nurturer of the creative spirit

Last month has been one of those months where the cults of achievement, ambition and prestige have all converged on me at the same time.

Personally, I barrel through life at an unsustainable pace, trying to be several kinds of things at once. I think that’s most of us, really. The tyranny of time coupled with decades of industrial conditioning has aggravated our relationship with time, and nixed our ability to distinguish between the important and the urgent. Pathological impatience is bone-deep, and we end up expecting results without wanting to put in the effort or to let things bloom at their pace. Marx said religion was the opium of the masses, but I’d say so is instant gratification.

When it gets like this, and when the hands of my clock seem like they are mocking me, even the simple act of slowing down becomes anti-mimetic, a rebellion. Any creative knows that to create is to dance between inspiration and expression.

But there’s a third factor in the mix — one which feels rare in a world that, to quote Milan Kundera, sees speed as a form of ecstasy. I could only put my finger on it when, seeking refuge from illusory urgencies, I turned to my well-worn copy of Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. In one letter to budding poet Franz Xaver Kappus, Rilke writes:

Being an artist means, not reckoning and counting, but ripening like the tree which does not force its sap and stands confident in the storms of spring without the fear that after them may come no summer. It does come. But it comes only to the patient, who are there as though eternity lay before them, so unconcernedly still and wide. I learn it daily, learn it with pain to which I am grateful: patience is everything!

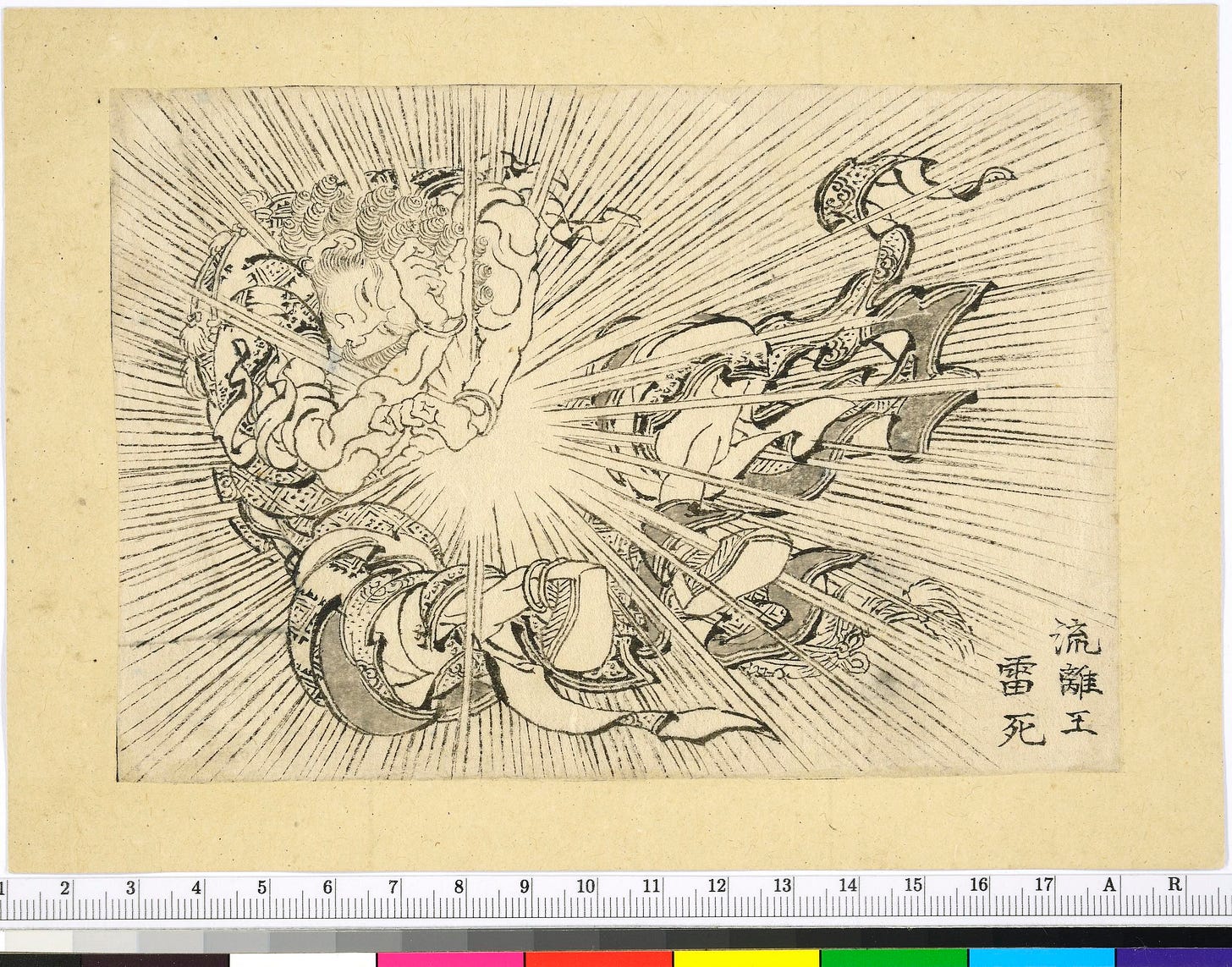

If inspiration is the defibrillator of the creative spirit, then patience is its nurturer. I sense this most deeply in the works of Hokusai, the ukiyo-e master whose paintings have plastered walls from established museums to first-year dorm rooms.

Although most well-known for his woodblock print Under the Wave off Kanagawa (popularly called The Great Wave), Hokusai produced a staggering 30,000 works in his lifetime. He began drawing at the age of six; for the next 80 odd years, his brush never stopped moving. His works, produced over two centuries ago, are ubiquitous today — a ubiquity that begs explanation.

He was a sympathetic observer of contemporary society, an artist who did not let the travel restrictions of Edo (modern-day Tokyo) set limits on his imagination. No work is more exemplary of this than his extraordinary, meticulously crafted illustrated book, One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. The unhurried strokes belie the lifetime of meditation it would’ve taken to produce a body of work centred on one primordial subject.

For me, this collection reflects a deep understanding that beneath the surface of the ephemeral lies a reservoir of boundless significance. One Hundred Views feels less like a pursuit of greatness and more like a gentle uncovering, an unfolding of the world’s hidden tales. It feels like one could get to that only with patience and presence. Indeed, he writes in the postscript to volume one:

...until the age of 70, nothing I drew was worthy of notice. At 73 years I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects and fish. Thus, when I reach 80 years, I hope to have made increasing progress, and at 90 to see further into the underlying principles of things, so that at 100 years I will have achieved a divine state in my art, and at 110, every dot and every stroke will be as though alive…

Speed and efficiency are tempting promises. But there is much to be said about the joy of claiming something for yourself, slowly, intentionally, patiently. There is much to be said about the journey of doing and being, because that’s what gives life—and art—its meaning.

Beautiful. Maybe you’ll enjoy this quote from Cormac McCarthy as much as I do: “The thing you are dealing with—time—is immalleable. Except that the more you harbor it the less of it you have. The liquor of being is leaking out onto the ground. You need to hurry. But the haste itself is consuming what you wish to preserve.”