committed seriousness creates its own gravity

or, you can just take things seriously

Did someone forward this to you? Subscribe to get future essays directly in your inbox.

A lot of life advice I’ve come across always rings with the undertone of “don’t take things too seriously”. I’ve always been someone who takes things seriously, so this does feel a little personal. When someone tells me not to, here’s what I hear: Don’t make others uncomfortable with your intensity. Don't put yourself in a position where you might fail. Don’t ask for too much from yourself, from anyone around you, from the world. There's safety in treating everything with equal doses of ironic distance.

Insofar as this advice stands for staying flexible and avoiding perfectionism, it makes sense. But I think it’s morphed into this ugly shield against conviction, and mollycoddles us away from the vulnerability of caring deeply about something. I refuse to believe that you can get through life in an interesting way without taking anything seriously and being unapologetic about it.

Granted, I’ve probably been radicalised by the thousands of books I’ve read all my life. When you grow up on a diet of J.R.R. Tolkien, Diana Wynne Jones and C.S. Lewis, it's pretty solid evidence that something remarkable emerges only from committed seriousness.

The metaphysical weight of committed seriousness is a curious thing. When someone takes an idea seriously enough, it begins to acquire its own gravity. This is usually my first thought when I encounter a piece of modern art, where the most common critique is “I could do that”. Yes, technically we could, but what we completely miss is that someone had to first take the possibility of doing it seriously. The apparent simplicity of the act obscures the staggering shift in perspective the artist needs to make it possible in the first place.

This works recursively, like a fractal of possibility. Each person who claims the space to do something serious expands the field of what others can imagine for themselves. The systems, institutions, and paradigms we operate inside, without a second thought, all started as someone's "thing" that they took seriously enough to bring into being. Reality, in many ways, is socially constructed through these countless acts of committed seriousness.

They don't have to be huge things, either. For example, I recently started an independent culture magazine called Patina. It isn’t The New Yorker, and probably never will be. But it has shifted the fabric of my and my community’s reality a little bit, becoming another publication that intentionally prioritises long-form reading and anti-advertising stances. Each deliberate stance like this adds to the texture of what's possible.

A tiny independent magazine in one corner of the world, taken seriously enough, exerts its own kind of force on reality, creates its own kind of truth through the sheer fact of its committed existence. I experienced this shift with Kindred Spirits as well: for a long time, I thought of it as "just something I'm writing." But there's an inherent power in claiming that space for your thing and what it makes you. This is a newsletter read by thousands, and I am a writer. Patina is a serious publication, and I am its founder-editor. It's not necessarily about claiming an "identity", because that comes with its own rigidity. I think it's about making that semantic claim that creates a framework for committed action. Less "I am a writer" and more "this is writing that I take seriously." Your thing becomes a reference experience that changes how you relate to everything else.

The space of what we can do is theoretically vast (even with the rules and ethics that govern us). But our actual sense of what’s possible tends to be remarkably constrained. When we think about what we want our lives to become, we tend to look through bifocal problem-centric glasses. We see problems and either ignore them until they fade from sight, or fix them in ways that satisfices.

Choosing the second path often results in a lot of chafing; it's very hard to be serious about something in a system that doesn't care as much as you, or cares about different things. This isn't to say you can't be agentic in a system designed by someone else. You can, but it is typically capped, or it is at the mercy of someone else's permission.

But I think we very rarely consider the agentic third alternative: taking the bifocal glasses off. Looking for opportunities to change the system or environment to such a desirable state that those problems cannot and will not arise. Committed seriousness to an entirely different script.

What fascinates me is how committed seriousness is easier with dramatic changes than when we’re changing smaller things about our lives. There's a kind of inertia at play. It's harder to maintain committed seriousness about smaller things because they seem too minor to deserve that level of attention. But the size of the undertaking doesn't change the essential nature of what's required: you have to believe that your judgment about what matters is worth honouring. Finding that third path often requires taking yourself seriously enough to create new frameworks, rather than just excel within existing ones. This is how we collectively expand what's possible.

It takes a particular kind of courage to pour energy and attention into something that you can't yet fully explain or justify to others. Committed seriousness requires a stubborn blindness to conventional metrics of success or importance. You have to be willing to treat something as significant purely because you've decided it is.

The world has enough casual observers. What it needs is more people willing to take things seriously enough to reshape what we think is possible. Think about this: What corner of reality is waiting for the weight of your seriousness?

Motifs that came to mind as I wrote this

visakan veerasamy: Visa is probably one of the first people who comes to mind when I think of taking things seriously, but taking yourself lightly. Here’s an excerpt from one of his essays (where he mentions he was also radicalised by books and the library):

When I say serious I don’t mean solemn and tedious.

I mean something closer to ‘dynamic persistence’, and a sense of humor is often critical to that. It’s hard to persist for a long time if you ‘take yourself too seriously’. You become rigid, stiff, the opposite of dynamic, and eventually you bang up against something that breaks you one way or another, because you weren’t able to back down, or laugh it off.

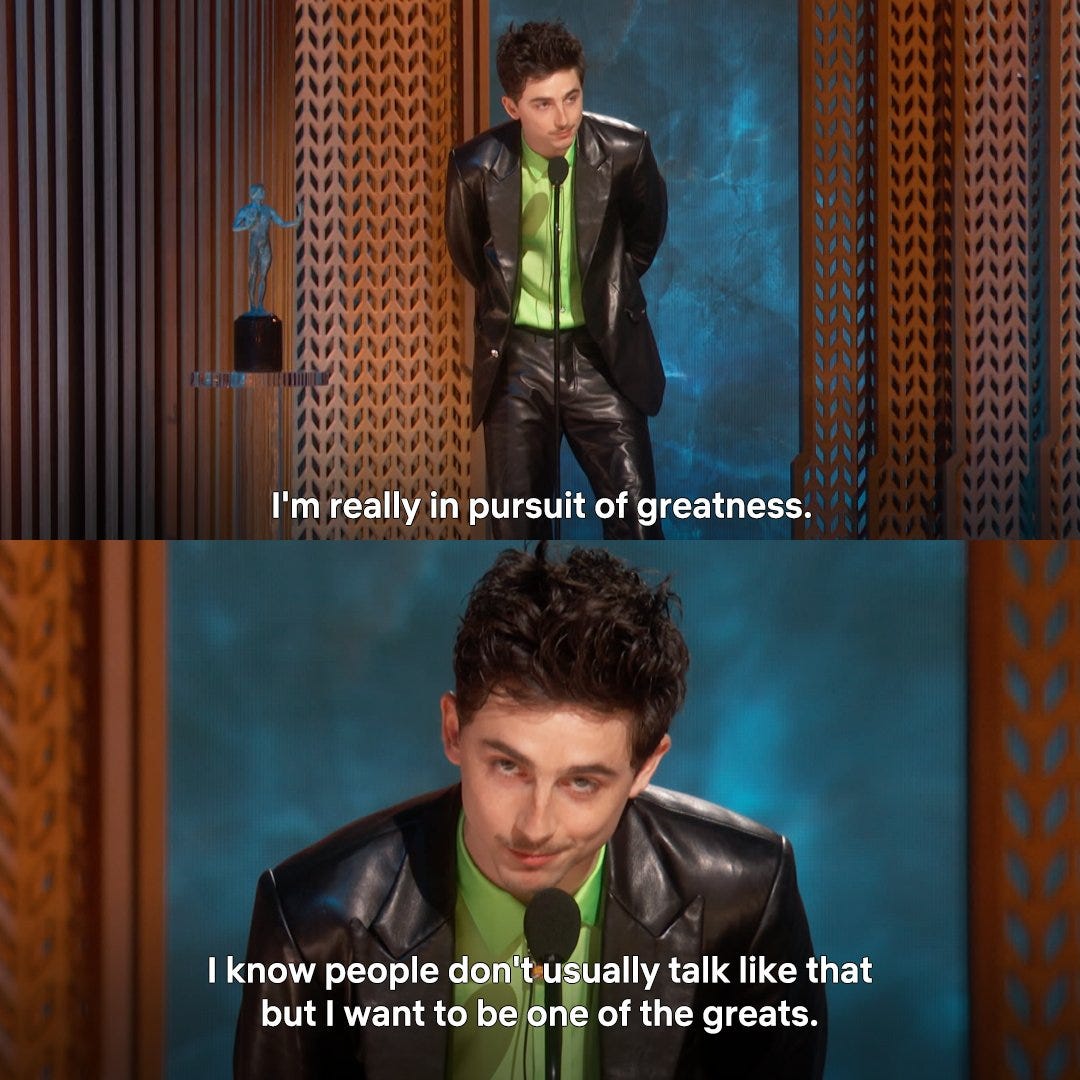

Timothée Chalamet’s SAG Awards speech. I love how unapologetically he delivers it, and how he acknowledges that people don’t usually talk like this:

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. When faced with a beautiful waterfall, conventional wisdom suggests building a house with a view of it. Wright, instead, made the house a part of the waterfall. He took an impossible idea seriously enough to bring it into being. Fallingwater is now a reference experience for thinking about how buildings and nature could coexist.

"What corner of reality is waiting for the weight of your seriousness?" is such a juicy question! Love it

Oh man, I am moved in ways I cannot possibly put into words.